Fitz Bits: Recursion Explained

This blog post is part of an ongoing series of computer science topics called Fitz Bits. Fitz Bits aims to explain high-level computer science concepts in simple, plain words.

Table of Contents

You may have heard about recursion in your coding journey. Often reserved for tech interviews and more complex coding problems, recursion can be a tricky subject to explain.

But I’m going to try anyway because I think that it’s one of those tools you can keep in your toolkit as a developer no matter which language you use. It’s a cross-language skill. And with the pace at which languages and tools come and go in development, cross-language skills are one thing you can hold onto throughout your career!

What is recursion?

If you’ve ever started a programming language, one of the first things you learn about are loops: statements that allow you to repeatedly run some block of code.

1

2

3

while (true) {

// I'm a block of code that runs infinitely!

}

In the example above, we have a while loop that runs over and over again and never stops!

On its own, recursion kind of does the same thing as loops but is just structured differently. Put simply, recursion is when a function calls itself.

1

2

3

4

5

function run() {

run();

}

run(); // calls function infinitely!

Just like loops, recursion allows you to run code over and over, and by default, it will never stop. In the example above, if you call run();, that will call run();, which will call run();, and on and on infinitely.

Adding a stop condition

Of course, we never want our code to run infinitely because that will crash our program. That’s why, with both loops and recursion, we need what’s called a stop condition.

You’ve likely encountered a stop condition with loops before:

1

2

3

4

5

6

let stopCondition = 10;

let counter = 0;

while (counter < stopCondition) {

// I'm a block of code that runs 10 times!

counter++;

}

The stop condition for the while loop is counter < stopCondition, which stops the loop when counter reaches the stopCondition of 10.

Recursion also needs a stop condition:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

function runTenTimes(n) {

if (n >= 10) {

// STOP!

} else {

runTenTimes(n + 1);

}

}

runTenTimes(0); // calls function 10 times!

The stop condition in our recursive function is our if (n >= 10) statement. When we call runTenTimes(0);, that will recursively call runTenTimes(1);, which will call runTenTimes(2);–until we reach runTenTimes(10); where the function will stop.

I still don’t get it… Explain recursion to me again

At this point, what I’ve said might be hard to wrap your head around, so let’s try again from a different angle.

1

2

3

function add(a, b) { return a + b; }

add(1, add(1, 1));

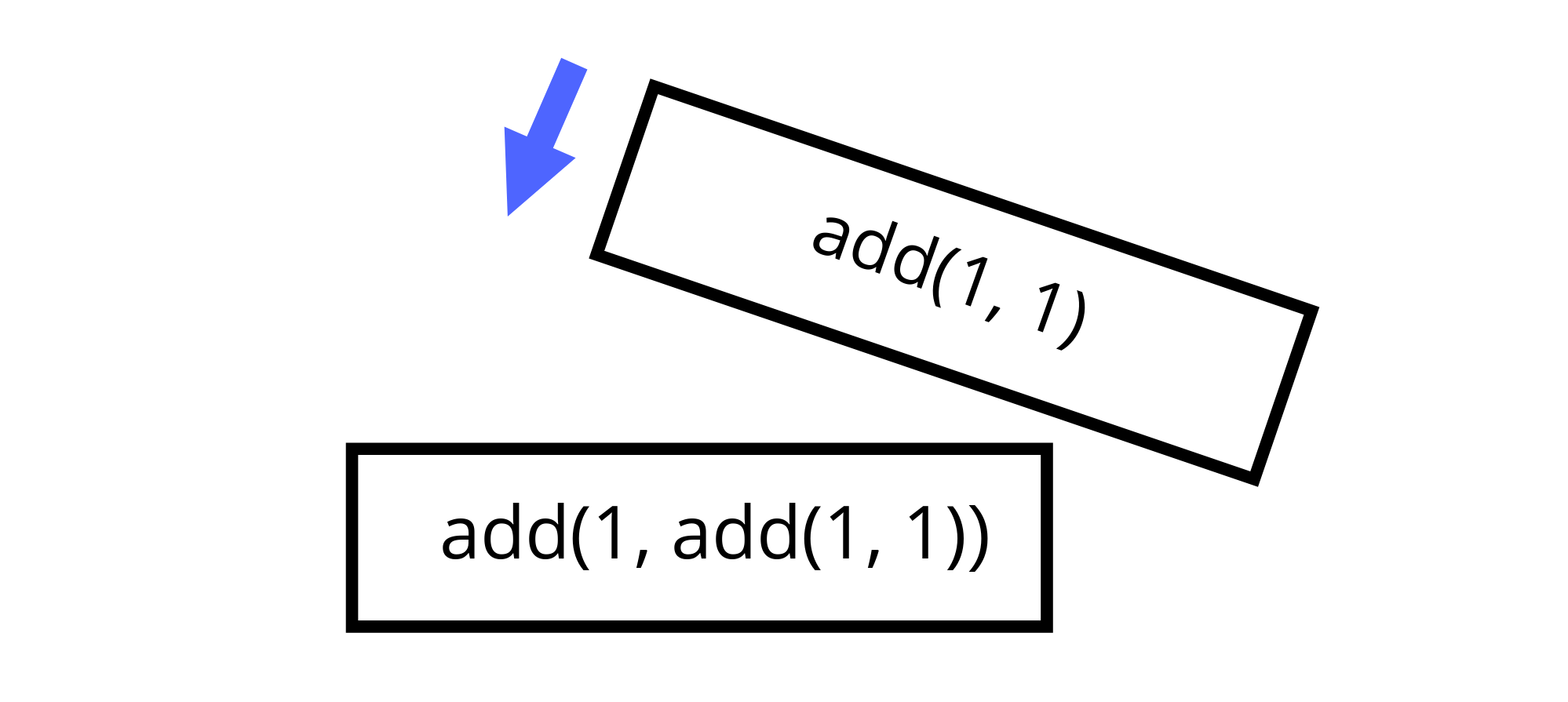

Take a look at the above function call. Notice how we nested our add() function inside another add() function?

When our code runs, what happens is it will call the outer add(1, add(1, 1)) function. However, in order to complete this function, it has to run the inner add(1, 1) function first.

This is known as the call stack. Every nested function creates another level on the call stack. It’s a way for your computer to keep a memory of each function that gets called, so when a nested function call completes, the computer is able to return to the previous function call.

So how does this relate to recursion? Recursion basically works the exact same way as nested function calls!

You can visually think of recursion as a mountain, where the top of the mountain is the highest point of the recursive call stack–which is defined by the stop condition! (Without a stop condition, the mountain will go up infinitely and never come back down, looking more like stairs instead.)

(You can also think of recursion as a spring, stretching further out until it reaches its limit, and then it pulls itself back in.)

When do you use recursion?

The fact of the matter is that loops can basically do the same thing that recursion can do. So why use recursion at all?

The main reason to use recursion comes down to code comprehension. Some coding problems are just easier to read, understand, and solve using recursion over loops.

One such coding problem that recursion works super well with are tree data structures. Most developers know at least one type of tree: the DOM or Document Object Model. (We’ll return to the DOM in a moment.)

Imagine you have a flat list of livingThings.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

const livingThings = [

{ id: "animals", parent: null },

{ id: "snake", parent: "reptiles" },

{ id: "plants", parent: null },

{ id: "cheetah", parent: "felines" },

{ id: "evergreen", parent: "trees" },

{ id: "felines", parent: "mammals" },

{ id: "reptiles", parent: "animals" },

{ id: "trees", parent: "plants" },

{ id: "mammals", parent: "animals" }

];

If you notice, this data can actually be represented as a tree of parents and children! Some of the elements have a parent of null, meaning they are at the top of the tree. Then their children branch off below them and their children’s children too.

The trouble is that the data isn’t actually structured as a tree. We can imagine the tree, but in reality the data is laid out flat. Parents and children aren’t structurally connected.

Recursion gives us an elegant, clean way to structure our data as a tree:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

function convertToTree(list, parent) {

const treeNode = {};

list.forEach(item => {

if (item.parent === parent) {

treeNode[item.id] = convertToTree(list, item.id);

// recursion happens here!

}

});

return treeNode;

}

When we call convertToTree(livingThings, null); (we pass null because we want to start at the top of the tree), the data gets spit out as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

{

"animals": {

"reptiles": {

"snake": {}

},

"mammals": {

"felines": {

"cheetah": {}

}

}

},

"plants": {

"trees": {

"evergreen": {}

}

}

}

In under 10 lines of code using recursion, we can take a flat list and convert it into a tree! (If you’re confused how convertToTree() achieves this, I would recommend running through the code line by line to get a handle of what’s happening.)

Again though, why does that matter? Well, many of us as developers will find ourselves interacting extensively with the DOM in our browsers. Given that the DOM is structured as a tree, knowing about recursion just gives us more options when controlling or moving through the DOM.

Summary

At the end of the day, recursion is another tool in our toolkit that we can make use of. As you grow as a developer, you’ll learn when recursion makes the most sense to use in your code. It won’t necessarily fit every use case, but it’s a great cross-language skill to carry with you wherever you go.

More Details

There’s even more at play in recursion. This article on using recursion safely touches on some of these topics and more:

- Stack overflow

- When recursion makes too many additions to the call stack, sometimes you run into a computational issue called stack overflow.

- Tail call optimization

- This is a method to avoid using the call stack in recursion, allowing you to also avoid stack overflow.

For a general overview of what I said in this article and more, Mozilla Developer Network (MDN) has a section on recursion.